After Winning Big in Levy votes, Chester Invests in Unregulated Surveillance Installation

CHESTER TWP - After a November election which solidified infrastructure and police funding for the small township of Chester, the trustees have voted to approve a not insignificant expenditure which would install Flock Cameras throughout the area, setting up an unregulated surveillance system to monitor the quiet town.

While Police Chief Craig T. Young waxed poetically about the benefits of linking the township up to federal databases to “stop crime”, Young was tight lipped on how these devices work and the greater potential impact to privacy for the average citizen.

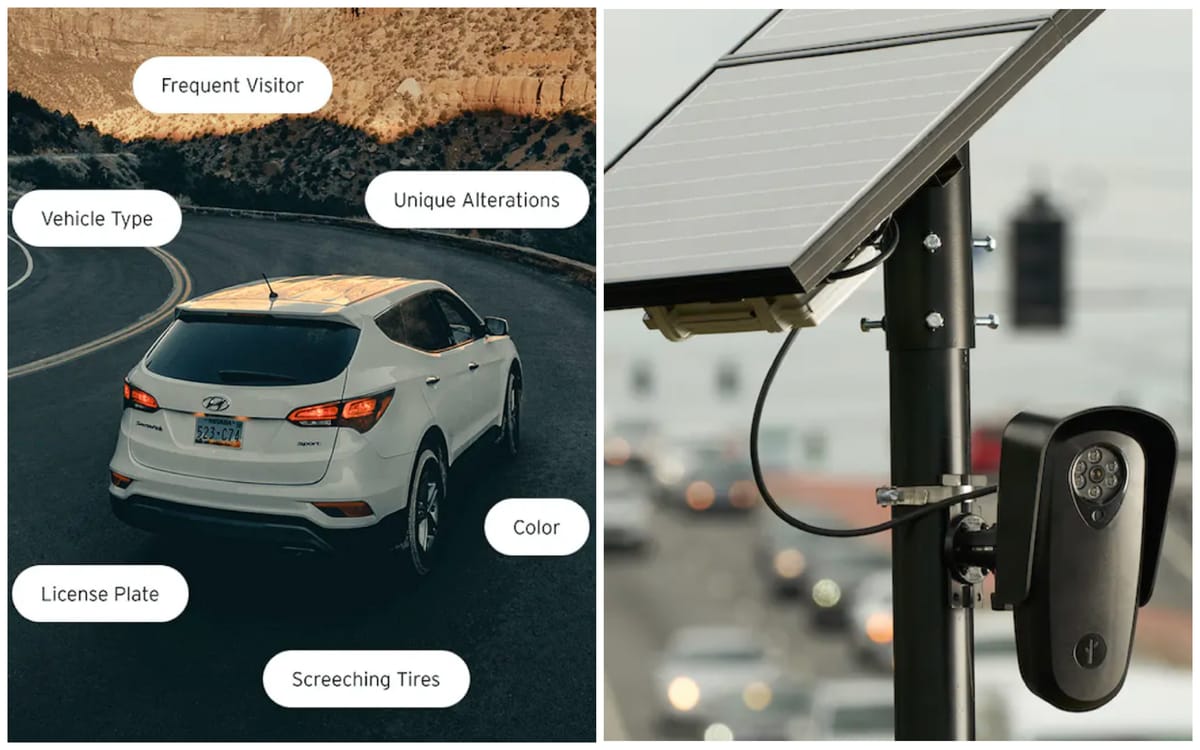

Flock Cameras are essentially license plate readers that take information pertaining to your comings and goings throughout any town that has them to share it with a local and national database accessible to other agencies also hooked into the Flock system. While the goal of using Flock is to track wanted criminals who may be crossing into the Chester Township limits, the unspoken cost of that is the unregulated surveillance of you, the resident, contributing to an information database of your comings and goings into an AI-driven database to correlate and monitor you.

According to an article from Vice.com, Flock cameras give local law enforcement agencies access to the “Talon” network, which links the cameras to national databases of local and federal agencies across the country. Unlike some states which regulate the usage of public surveillance mandating non-pinged plate information be deleted within minutes of collection, Ohio has no such regulations, meaning your information is collected and stored for as long as desired by the agency collecting it. Tracking through this system happens near instantaneously and is maintained by the agencies collecting it, until it is stored in cloud based servers. This has led historically to many issues including when local law enforcement agencies fail to update the system registries of things like when a stolen vehicle is repossessed. This has led to police enforcing federal warrants on law abiding citizens without just cause.

The growing public-private partnership of Flock has additionally has used local law enforcement agencies to boost their sales through PR campaigns written and organized by the company but rolled out by government agencies, helping to blur the lines between what is considered good conduct by LEOs.

Further, while Flock advertises itself as being a locally driven device that puts control of the surveillance in the hands of the customer, its partnership with Axon, flies in the face of that. Axon is the Blackrock controlled military contractor that develops weapons surveillance technology for both the U.S. military as well as foreign nations abroad such as the IDF, where their AI based technology, labeled “The Gospel” was used to systematically bomb civilian targets in Gaza contributing to claims of human rights violations internationally.

While the longer-term questions loom on whether or not introducing AI driven monitoring technology with ties to foreign governments into our communities is a good idea, the more immediate questions posed by whether local agencies have enough good faith to wield said technology is ever present. It has long been known that surveillance technology is often abused by government agents for personal purposes and some have even been caught doing it. The question remains on if the Chester Police department has proven themselves trustworthy enough to wield this technology responsibly given previous incidents.

The War on Terror brought with it unparalleled surveillance into the daily lives of American citizens under the guise of safety and security. From tracking phone conversations, email correspondence and utilizing social media as an alternative to Lifelog and the Information Awareness project, which uses AI to create a digital map of your disposition in an attempt at “preventing crime” before it happens.

Once introduced, these surveillance apparatuses never go away and are typically only expanded upon. So it is no surprise that Flock additionally has sought to expand its technology from visual surveillance to audio as well. Their development of Raven audio recordings adds microphone recording to their video surveillance devices, introducing a whole new way to define government surveillance into the community. Its official usage is for tracking shootings in an area, however the implications of the technology do not stop there. The ability to triangulate sounds of any sort, powered by AI means individual conversations can be zeroed in on in your neighborhood, especially given how closely the microphones are place to the ground, introducing concerning questions on.

The usage of these devices brings about legal questions which the Supreme Court has weighed heavily on.

In two cases involving police use of digital technologies to track or aggregate peoples’ locations and movements, the Supreme Court has stated that “individuals have a reasonable expectation of privacy in the whole of their physical movements” because of the “privacies of life” those movements can reveal.

In United States v. Jones, a majority of the court wrote that using a GPS tracker to follow a car’s movements for 28 days constitutes a Fourth Amendment search, stating that the ability to “secretly monitor and catalogue every single movement of an individual’s car for a very long period” raised serious concerns. More recently, the court held in Carpenter v. United States that when police request seven days or more of a person’s historical cell phone location information from a cellular service provider, a warrant is required because of the “deeply revealing nature” of these digital location records, their “depth, breadth, and comprehensive reach,” and the “inescapable and automatic nature of [their] collection.”

These rulings expressly rejected the argument that the public nature of the targets’ movements meant they had no legally significant expectation of privacy. Automated license plate readers raise the same concerns the court addressed in Jones and Carpenter, namely that they facilitate detailed, pervasive, cheap, and efficient tracking of millions of Americans in previously unthinkable ways.

There is no “victory” in these battles against private citizens, they are endless. So potentially the biggest question is when the residents of Chester voted to approve levies for infrastructure and law enforcement, under the guise that voting down these levies would drastically impact the community, were they aware that the extra money would help construct a digital surveillance apparatus in their town? Is that really what they voted for?